A great movie about Xuan Zang, the most celebrated and influential of all the Chinese monks who travelled to India and brought back Buddhist scripture during the Tang Dynasty in his “Journey to the West”.

Chinese-Indian historical adventure of Xuanzang’s seventeen-year overland journey to India during the Tang dynasty in the seventh century.

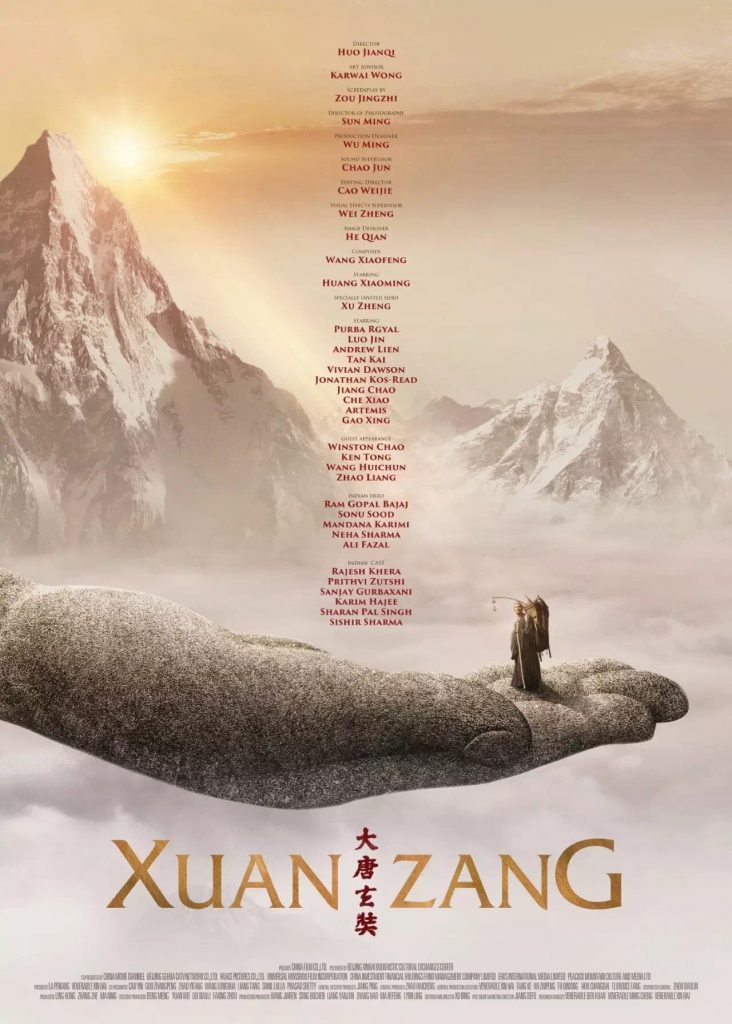

Xuanzang or Xuan Zang is a 2016 Chinese-Indian historical adventure film based on Xuanzang‘s seventeen-year overland journey to India during the Tang dynasty in the seventh century. The film is directed by Huo Jianqi and produced by Wong Kar-wai. It stars Huang Xiaoming, Kent Tong, Purba Rgyal, Sonu Sood and Tan Kai.

Xuanzang, born Chen Hui / Chen Yi, was a Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator who traveled to India in the seventh century and described the interaction between Chinese Buddhism and Indian Buddhism during the reign of Harsha.

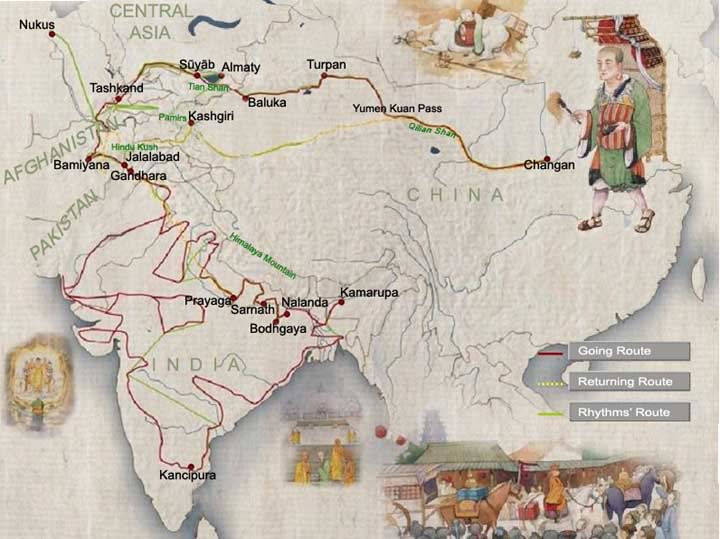

Traveling through the Khyber Pass of the Hindu Kush, Xuanzang passed through Kashgar, Khotan, and Dunhuang on his way back to China. He arrived in the capital, Chang’an, on the seventh day of the first month of 645, 16 years after he left Chinese territory, and a great procession celebrated his return.

https://sogdians.si.edu/sidebars/xuanzang/

Traveling by night and without a guide, Xuanzang arrived in Liangzhou 涼州 (modern-day Wuwei 武威市, in Gansu Province 甘肅省) at the western frontier of China. It was the terminus of the route to and from Central Asia as it skirts the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert . There he spent a month preaching, before being invited by the king of Turfan , a devout Buddhist. Realizing that the king planned to detain him for life to be the ecclesiastical head of his court, Xuanzang staged a hunger strike and was eventually allowed to continue his journey.

Thus, in 630 Xuanzang resumed his travels, armed with introductions to all the rulers along his route (including the ruler of the Western Turks who controlled the region up to India). No longer a fugitive, he was now a pilgrim with official standing. Managing to avoid robbers and other hazards, he reached Sogdiana, where he spent time in Samarkand . While in Samarkand, he went in search of Buddhist temples, only to find them abandoned. Xuanzang describes how, on investigating one of the monasteries, his disciples were attacked by a group of Sogdians who believed in Mazdaism. Xuanzang eventually gained an audience with the king of Samarkand, who saw that the locals were punished for their assault. Having won the king’s favor, the pilgrim was allowed to hold an assembly at which he ordained a number of new monks.

Heading south, Xuanzang passed through Bactria (modern-day southern Uzbekistan and northern Afghanistan), and finally reached northern India. He remained in India for over a decade, spending the main portion of this time at the Nalanda Monastery, southwest of modern Bihar , but also traveling throughout the region, touring monasteries and other Buddhist sites. All the while, he studied Buddhist texts and engaged in religious and philosophical debates with Hindu Brahmins, Jains, and heterodox Buddhists. During this time he acquired a masterful knowledge of Buddhism, and collected numerous Buddhist manuscripts, relics, and statues to carry back to China.

In 643 Xuanzang began his return via Central Asia, crossing the Pamir Mountains to Dunhuang after gaining permission from Emperor Taizong to return. He arrived in Chang’an in the first month of the Chinese lunar year 645 to great celebration. Xuanzang then devoted the rest of his life to translating the Sanskrit manuscripts he had collected. During the same time, he wrote an account of his travels, The Great Tang Records on the Western Regions. The work provides a firsthand glimpse of the cultures, politics, and religions along his route. Indeed, Xuanzang’s narrative is one of the few surviving primary sources on the Sogdians. However, the narrative should be read with a certain caution, since some of the events he described seem unlikely, or certainly embellished. Take, for instance, Xuanzang’s claim that the King of Samarkand warmed to him so quickly that he was allowed to preach and convert locals to Buddhism. It is quite probable this is exaggerated; more likely, the king wished to impress Xuanzang to gain China’s support in case Samarkand broke from Turkish rule. Still, Xuanzang’s account remains one of the most illuminating and important texts we have about life along the Silk Road.

He goes on to describe how he had to travel like a fugitive, under cover of darkness, to dodge the border guards. The journey took him along the Silk Road (what the Chinese called the Road Carrying the Jewel of Truth), through the Gobi Desert, over the mountains into Afghanistan, and then through Pakistan into India. Once there, he made his way to Bodh Gaya to see the Bodhi Tree where the Buddha attained enlightenment:

“And when I saw it, I lay on the ground and shed many tears.”

Xuanzang stayed in India for many years, travelling and studying the scriptures. When he returned to China, he brought back 657 books in 570 packages on 20 pack horses. The Great Wild Goose Pagoda in Xi’an was built to house the manuscripts, written in Pali on palm leaves. There are only a few fragments left now as most were lost in various wars and revolutions.

Xuanzang spent the rest of his life translating the scriptures, and the Emperor forgave him for leaving China without a permit and asked him to become prime minister and help run the country. But Xuanzang wasn’t interested and turned him down, saying:

“It would be like taking a boat out of the water. Not only would it cease to be useful, but in time, it would rot away.”

https://www.ancient-buddhist-texts.net/Maps/Silk-Routes/Chinese-Pilgrims.htm

Xuanzang, 600-664

Xuanzang is the most celebrated and influential of all the Chinese monks who travelled to India in search of the Dharma. He was born around 600 and started his journey in 629. After crossing the Taklamakan desert and then the Pamir mountains he made his way to Kashmir, where he studied for two years, before heading down to the Ganges plains and into the Buddhist heartlands.

He followed further studies at Nālandā University for some years, and became a great teacher himself, before going on pilgrimage round India. On return to Nālandā he won a great debate, and finally decided to return to China with his treasure trove of scriptures, relics and sacred images.

After many adventures and life-threatening incidents he arrived back sixteen years after leaving. He spent the rest of his life translating the texts he had brought back.